What store did you love to go to as a child?

What keepsakes or family heirlooms do I treasure most?

The first keepsake that comes to mind is what remains of the beautiful and fragile set of fine ceramic dishes my father brought home from Japan after World War II. I still have a few pieces — a pitcher without its top, a serving bowl, and a cup — all beautifully trimmed in gold.

When our dad was in the Navy, he served on several warships in the Pacific theater. During the formal end of World War II — marked by the Japanese Instrument of Surrender signed on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945 — our father was aboard an ammunition ship. That ship was ordered to leave the bay during the ceremony, since no one wanted to risk an incident like an explosion that could have disrupted the proceedings.

During that time, our dad was able to purchase a full set of fine china

, including serving dishes, cups, saucers — maybe fifty pieces in all. The few that remain today are a vivid reminder of what can happen to such delicate treasures.

In our home in Maine, we had a corner cupboard with shelves running all the way to the floor. It was about 1947 (before or just after I was born, I imagine) when Dad returned home. He went to work, and Mom was in the kitchen. My older sister, who was just learning to walk, was toddling around the house.

Mom said she began hearing some strange sounds — a crash, a tinkle, and a flush. At first, she didn’t think much of it; it wasn’t very loud, so she dismissed it. But after a while, she decided to investigate.

To her surprise, she found my sister methodically taking piece after piece of the fine, delicate dishes from the cupboard, carrying them into the bathroom, and smashing them into the toilet. She must have liked the tinkling sound they made! Then she would flush — and our fine china went right down the drain.

Much of the set was gone that day, but the few surviving pieces have become cherished keepsakes — reminders of both my father’s journey and one unforgettable family story.

What Did You Find Surprising When You Started Your First Job?

My first paying job was picking potatoes when I was thirteen (seventh grade). In our area of northern Maine, school started a month earlier than in most of the country so that all the kids could take a month off to help bring in the harvest.

Out in the field, we waited for the digger to come by. All of us — from eight to eighty — stood in line beside the rows to be dug. Each of us had a section to pick after the digger went by. The smaller kids had about ten feet to cover, while the able-bodied workers got forty feet or more. We had to have our section picked clean before the digger came by on the next pass. If we didn’t, someone would get more and I’d get less.

Medium-Sized Baskets

The younger kids had small baskets; the older ones got bigger ones. Each of us was given a stack of tags, about one inch by three inches, with our number on them. We filled the baskets, then dumped them into barrels and stuck the tag on the barrel. As a Presque Isle farm kid, I always considered those baskets works of art. I knew I couldn’t make anything like that! They were made of ash wood and were incredibly rugged — I’ve seen a few survive being run over by a truck (and a few that didn’t).

Baskets and Barrels

A two-row digger would dig up two rows at a time. We picked up the potatoes, filled the basket, and dumped it into the barrels, then the truck followed behind to collect them. The truckers gathered our tags so they wouldn’t get lost. As mentioned, farmers preferred that pickers fill barrels while they were laid on their sides until about half full — dumping into a standing barrel tended to bruise the potatoes!

We earned twenty-five cents for each filled barrel. I always loved it when you were down on your knees and accidentally squashed a big, black, juicy rotten tater. Not only were your pants wet and frozen, but you stunk like heck warmed over! When the digger broke down, we’d build a small fire and roast potatoes in the coals. They never came out fully cooked, but we ate them anyway — semi raw, coals, ash, and all.

The number of baskets it took to fill a barrel depended on the size of the basket. The youngest kids, eight to ten years old, had small baskets, so it took many to fill a single barrel. It didn’t matter how plentiful the crop was — it all came down to basket size. When you used a barrel on its side, you could fill it halfway before standing it upright to finish. Otherwise, the potatoes would just roll right back out. The little ones often needed help from us bigger kids (I was already six-foot-two at thirteen) or from adults, since those half-filled barrels were heavy.

The Worst

The worst was when we picked seed potatoes — the kind later cut up for replanting. We’d stand in the yard in thirty-degree weather while they sprayed us down with water and chemicals to prevent disease. Cold and soaking wet, off to the fields we trooped. You probably wouldn’t see anyone doing that to kids today!

Moving Up

The next year, when I was fourteen, I worked on the back of the stake truck. The truck had posts along the sides with chains between them to hold the barrels in. At first, we lifted the barrels up by hand, but later the farmer installed a hoist with a clamp to raise them. When they were up we rolled them to a final position, not so easy on the back of a moving truck bouncing across the field. With the new system, only two of us were needed on the back of the truck instead of three, and we could work all day.

One day around 2 p.m., our cocker spaniel & Irish setter mix was lying out in the field with us, enjoying the sun. A truck driver was coming back for another load, but he was going too fast. People were shouting, “Slow down!” Unfortunately, he didn’t see my dog and ran over her. She yelped once and died instantly. The farmer was so sorry — he sent all of us home for the day.

When I was fifteen, the farmers began using harvesters, so we no longer had to pick potatoes off the ground. The potatoes came up a conveyor belt where workers picked out stones and vines — the rocks went into a rock bin, and the vines went over the side. I worked the harvester for a while before being promoted to driving the bulk trucks.

I didn’t have a driver’s license yet at fifteen, but I learned on two types of trucks: one with eight gears and another with ten. That many gears were needed. First to move at very low speed beside the harvester, then medium gears when hauling full loads back to the barn, and lastly the higher gears when driving empty down the road back to the field. Once, backing up to the harvester, I accidentally hit the rock box. The farmer wasn’t upset — he just said it happens sometimes and fixed it.

Lessons Learned

We learned how hard money comes — and that we didn’t want to do this for a living! None of us liked it, but it was how we earned money for school clothes. It never occurred to us to tell our parents we didn’t want to work. It was expected. No questions or complaints allowed. Off you went before dawn — those potatoes weren’t going to pick themselves.

Looking back now, what surprised me most was how much responsibility and toughness were expected of us at such a young age, especially the eight year old’s. We didn’t question it; we just did it. That job taught us about hard work, endurance (12 hour days), and teamwork — lessons that stuck long after the harvest was over.

In discussing this story with my sister Susan, she told me that SHE had picked potatoes too! I had not known that! She said she picked them for three years when she was 9. 10, and 11, and with the money she earned she bought Christmas gifts as well as her clothes! She said tht she bought dad a very nice shirt that he wore to special events!

Again, such responsibility and toughness were expected of us at such a young age!

What does a perfect day look like to me?

There are so many things that could go into that!

To begin with, it would have to start with having my daughter Amy around. That is the main ingredient. She makes any day go so well with her smile and upbeat nature. A PERFECT day would have to start with her.

Then you add the location:

If Seattle: Walking in the woods with the tall fragrent trees down to the water to watch the birds,

or kayaking up the creek. Or heading east to the desert and the petrified forest,

where she and I can climb up into a wind turbine, then come back through the quaint Bavarian village of Leavenworth.

Or going wall climbing.

In the evening, we could go to a science exhibit or up the spire.

If Florida: Starting out with me cooking breakfast, of an egg, cheese and spinach. then kayaking up Bear Creek and taking photos of the birds.

Then coming back and painting a portrait of one of them. Later, bicycling through the village of Gulfport around streets of nice homes and trees in the afternoon, Stop at the home with huge Ham radio antennaes. And then going shopping. We’d come home to watch one of the many movies I have.

If Alaska: Hopping onboard a Holland America ship,

enjoying fabulous meals,

great entertainment, and watching glaciers and wildlife glide by. Watching bald eagles,

bears,

salmon, seals, and all the other wildlife. We saw a momma and two baby bears up really close. Going up on a glacier and taking a dogsled ride would also be wonderful—if the weather cooperates.

If Greece: Amy and a friend a I taking a boat out to a Greek island that was once a huge volcano, climbing up and watching plumes of gas rise from the top.

Or taking a trip to see the monasteries perched on spires of rock.

Or a boat ride to the island of Delos to see the many lion statues and ruis of buildings.

Or climbing all over the Parthenon

and exploring the new museum that is built on stilts over an excavation and holds many nearby discoveries. With a stop at Delphi

to see if Pythia, the Oracle of Delphi, is in and can tell us what Apollo has to say. Then relax looking out over the ocean.

Any one of these would make a perfect day! And has!!!

What’s one piece of advice you’ve passed on to your daughter that means a lot to you?

I think the most important thing I ever passed on was this: once you give your word—once you commit to something—you hold to it, even when it hurts. You don’t walk away just because life gets messy or disappointing. A commitment is a promise, and a promise should mean something.

Amy understood that early in her life. She made a plan for herself: go to college, build a career, have a child, then step away from work for several years so she could then pour her whole heart into raising that child.

Then, when the time was right, return to work in a way that still allowed her to be present as a mother. She worked 20 hours a week so she could be there when her daughter got off to school and be there again when she came home. It was a brave plan, and she followed it with determination and grace. She didn’t just talk about commitment—she lived it.

She carried that same strength into her marriage. Her husband’s battle with MS was long, slow, and heartbreaking. MS is such a cruel, quiet thief; it takes a little more away from you each year. For more than twenty years, Amy stood beside him—steadfast, patient, loving. She and their daughter walked with him through every struggle, every decline, every hard day. And even now, long after he’s gone, she continues to honor him. When she hosts the Ham Radio Show each week, she does it in his memory, as a way of keeping a part of him alive.

It means more to me than I can truly say to see my daughter live her life with such unwavering loyalty and courage. She has not just kept her commitments—she has embodied them. And watching her do that fills me with pride, love, and gratitude beyond words.

Can you share a memorable volunteer experience that impacted you deeply?

One volunteer experience that changed me profoundly was my time with David.

Over the years I’ve taken part in many forms of service—teaching kids to build balsa wood bridges at USF for forty years, rescuing birds, mentoring students, feeding the poor, delivering meals, monitoring wildlife, serving as a Guardian ad Litem, even playing Santa in nursing homes. Each experience mattered and I have many memories of children I have saved. But none touched me the way David did.

David was a boy abandoned by his parents and left in the care of a grandmother who didn’t really want him either. She passed him from program to program—Boy Scouts, Camp Fire, county activities—anything to keep him occupied while she focused on dating. He had no stability, no one who was rooting for him.

I began spending time with him several days a week. We did simple things: sailing on the yacht I lived on at the time, trips to Busch Gardens, just having fun and giving him a sense that someone actually enjoyed being with him.

My 45 foot Hunter sailboat

One day, driving back from Busch Gardens, he commented on a billboard. What he said didn’t match the words on it, only the picture. That’s when it hit me—he couldn’t read. He was ten years old, and in fourth grade, but he couldn’t read basic words. Not even the word “Coke,” unless there was a picture of a can beside it.

I went to Haslam’s and bought first-, second-, third-, and fourth-grade reading workbooks. When I sat down with him, he insisted he read at a fourth-grade level. I told him we were starting at first grade, just to see where he truly was.

We sat in the boat cabin with the first page open. He couldn’t stay focused—his eyes wandered around the cabin, he’d jump up to look at something, he’d talk about anything except the workbook. ADHD or not, school had clearly never been a place where he felt success or encouragement. He had been moved from grade to grade without learning to read

After nearly an hour on page one, I finally said,

“David, it’s taken forty-five minutes and you still haven’t finished this page.”

He straightened up and replied,

“I can do better than that.”

That was the turning point.

A spark went off inside him. From that moment on, learning became a personal challenge—a game of beating his own time. Suddenly he wanted to know how many minutes each page took. He tore through every page of every grade-level book. And every bit of encouragement—“You did that in only five minutes!”—was gold for him.

Later, his teacher told me he had completely transformed.

He wasn’t disruptive anymore.

He had become a model student.

Years afterward, David called me just to say thank you.

Of all my volunteer work, that experience stays with me the most.

Because for the first time in his life, someone believed in him, and that he could do better—and he proved it himself.

What’s a funny story involving your siblings from childhood in Maine?

On my tenth birthday, we moved from Presque Isle, Maine to Gardiner, Maine. I remember the day clearly—not because of cake or balloons, but because there weren’t any. We were on the road to our new house, everything we owned packed up and moving us south to a new home, so a traditional birthday party just wasn’t possible. Instead, my parents surprised me a few days later with something even better: a brand-new bicycle, my very first one. To a ten-year-old boy, that bicycle meant freedom, independence, and endless afternoons riding the quiet streets and roads of a small Maine town.

Three years later, I had grown—dramatically. By the time I was thirteen, I stood 6 feet 2 inches tall and wore a size-13 shoe, towering over most kids my age and even a fair number of adults. My brother David was ten, Donald was eight, and the twins were six. With five boys under one roof, there was constant noise, motion, and good-natured chaos. Wrestling was practically a daily event, a mix of competition, laughter, and sibling pecking-order negotiations.

One day, the four of them decided it was time to take me down. They clearly believed that sheer numbers would compensate for the size difference. David positioned himself squarely in front of me, straining and pushing me backward. Donald wedged himself behind me, shoving forward with all his might. Meanwhile, the twins each grabbed one of my legs, pushing and pulling in opposite directions, faces scrunched up with effort and determination.

The funny part was that I didn’t have to do anything at all. I simply stood there as they all pushed against one another, their efforts perfectly canceling each other out. After a few moments, they realized what was happening and burst out laughing—especially me. It was one of those small, spontaneous moments that capture what it was like growing up in a house full of brothers: noisy, physical, occasionally ridiculous, and full of memories that still make me smile.

How did cycling or kayaking help you connect with the community or nature?

Cycling helped me connect only a little with the community, but kayaking has helped tremendously.

For several years, I have kayaked a two-mile route nearly every morning. Along this route, I have met many people and photographed countless birds. Over time, the kayak became more than exercise—it became a way to build quiet, meaningful connections with both people and nature.

My first regular stop was near the home of Alan and his wife. Alan had been part of a Presidential advance team, traveling around the world ahead of the President to set up communication systems. Through his work, he met four US Presidents, many heads of state, and numerous local officials. Alan and I developed a friendly relationship. He would often come out onto his rear deck to greet me, sometimes joined by his wife.

Over the years, we shared many small but meaningful interactions. Once, when I needed to use a bathroom, Alan showed me where it was. Another time, his neighbor was selling a small sailboat that was up on a float. I bought it—paying more than it was worth—and tied it to Alan’s dock. Alan and I went halves on an electric trolling motor so we could both use it. A friend and I took the sailboat out once; it sailed well, but it sank on the way back. I managed to get it back onto the float and eventually donated it to Eckerd College rather than try to repair it. Later, Alan bought my half of the trolling motor.

Alan and his wife volunteered at a Methodist church thrift store in Gulfport, and he occasionally invited me to church meals, which I attended a few times. We also bonded over shared experiences working for the federal government. Unfortunately, in 2024, Hurricane Helena destroyed the interior of their home. They had recently sold a farm in Sarasota and purchased a house in Bushnell, so they relocated there. Eileen recently saw Alan at the thrift store, and he asked her to pass along his greetings.

Further along my route were Scott and Lori. I often saw them on their rear deck. Scott worked for the power company and seemed to be home frequently. Over time, I watched as they built a pool and began spending much of their time around it. Before the presidential election, they displayed a Trump flag, as did many nearby homes and boats. After the election, the flags came down, and eventually all such signs disappeared from the area.

When the nearby marina proposed installing a fuel station, Scott and Lori were concerned about the environmental impact, especially since the marina is adjacent to a preserve. They asked for my help. I prepared foam core displays and a short speech and joined over 100 residents at a South Pasadena city hall meeting to protest. The marina had been denied a fuel dock years earlier, but with a new mayor and council in place, the proposal was approved with little discussion, despite the concerns raised.

Along the route, I also met many residents of the Sail Point apartment complex. All were friendly, often calling out from windows or sitting on the grass. I collected floating chairs and debris for them and shared my bird photos by email, which I send regularly to nearly 300 people. The complex had a wonderful kayak landing with rollers and handrails that allowed paddlers to exit without getting wet. Sadly, the apartments were flooded during Hurricane Helena, and the residents have not returned.

Further on, I met a family from Ukraine who had been in the U.S. for about a year after fleeing the war. They had two small children and a friendly puppy and were working to rebuild their lives here.

Another stop was a woman with two dogs that constantly fought each other. She often ran a concrete mixer filled with glass and sand, creating “sand glass.” She eventually gave me one of her art pieces made with beads and three pieces of the glass.

There was also a woman who had lost her seawall. She told me how much she enjoyed my bird photographs.

In a wider, pond-like section of the route, I often encountered “Nature John,” another kayaker. He was an accountant who lived on a tributary. When he disappeared for a while, other residents asked me about him. At Marian’s urging, I went to check on him and found him very ill, answering the door in his pajamas and looking frail. I have been meaning to check on him again. He has not been seen for a long time.

Further along, I met a couple who split their time between Canada and Florida. They told me they planned not to return and intended to sell their home. I met them both while kayaking and again while bicycling. They showed me how one room had once been a kitchen, but all the plumbing had been hidden in the walls so it could serve as an office.

At one point, a tributary that once fed into Bear Creek is now covered by a house. The man who lives there is very friendly and takes great care of his home and grounds.

Near the end of the route, a woman regularly feeds the ducks, which line up along her seawall. She also has two dogs.

Beyond that point there are no more homes—only vegetation. I have paddled quite far into this area, but eventually I stop where a massive fallen tree blocks the creek.

In all, the route up behind homes has been very conducive to making friends in this area. Without paddling I would never have met so many nice people and connected with the community.

There have been many special moments with my daughter—hiking together in the forests of the Northwest,

sailing, and traveling to Alaska to see glaciers and bears

—but the most meaningful recent one was a trip to Greece with her.

This was the best trip I have ever taken, and that is saying a great deal after more than fifty years of travel. What made it different was not just where we went, but that we experienced it together.

From the moment we left—flying first to Istanbul and then on to Athens—we shared everything: long days, early mornings, meals, and conversations. Each morning we sat down to breakfast together and talked about what we would see next. Those quiet moments mattered just as much as the famous places.

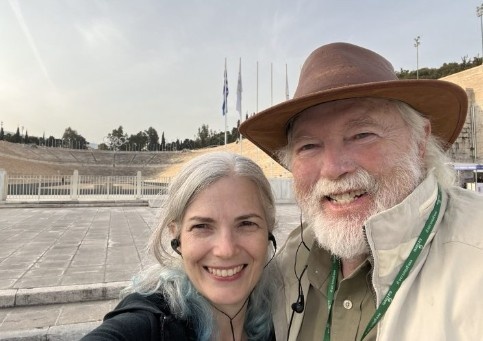

Walking through Athens, standing beneath Hadrian’s Arch, visiting the Panathenaic Stadium,

and climbing up to the Acropolis, I was struck by how naturally Amy moved through it all—curious, joyful, and eager to learn. Watching her take in the Parthenon and the surrounding ruins made me slow down and see them differently myself.

Whether we were climbing to the top of a volcano

or exploring ancient sites like the lions of Delos,

Amy was always smiling, always engaged. She brought energy and warmth to every place we visited. I realized how rare it is, as a parent, to spend uninterrupted time with your grown child—side by side, discovering the world together.

We learned together in museums, wandered through ancient buildings, and stood in awe of remarkable monasteries. Amy happily climbed over ruins that had stood for thousands of years

, and in those moments I felt both pride and gratitude. Pride in the person she has become, and gratitude for the chance to share something so meaningful with her.

That trip was special not because of Greece alone, but because it gave us time—real time—to be together. It is a memory I will carry with me for the rest of my life.

A Favorite Family Tradition from Growing Up in Maine

Growing up in Maine with my siblings, we had so many cherished traditions that shaped our childhood. Here are some of my favorites:

Christmas Traditions

Handmade gifts during lean years — When money was tight, we’d draw names and make gifts for each other. It taught us creativity and thoughtfulness over commercialism.

Original photo by Helen Berry

Clorized by Gemini (AI)

Christmas morning lineup — We’d line up at the top of the stairs, trembling with anticipation, until Dad gave the word: “Go!” Then we’d race down to open presents. Stockings with tangerines — Every Christmas Eve we hung our stockings, and Christmas morning we’d find a tangerine tucked in the bottom—a simple treat that felt magical.

Fresh tree decorating — We always had a real Christmas tree and made our own garlands by threading popcorn and cranberries in alternating patterns.

Food Traditions

Sunday ice cream ritual — Dad would buy a half-gallon of ice cream and cut it into eight precise pieces—one for each family member.

Birthday chocolate cake — Every birthday meant chocolate cake with peanut butter icing. No exceptions.

Mom’s Lolly Pop Shop — When Mom prepared for chocolate dipping, she’d buy 20 pounds each of dark, white, and milk chocolate. We’d eagerly ask for “just a bite.” She also made lollipops by pouring melted sugar into cast iron molds.

Thanksgiving and Christmas centerpiece — Mom would hand-mold a turkey from sugar and butter, serving it alongside brown bread and foamy sauce.

Sunday Adventures

Picnics in Canada — We’d cross the border for Sunday picnics as a family.

“Wagon Ho!” gatherings — Some Sundays, each family would pile into their station wagon and converge at a park for dinner before heading to Evening Service together.

Daily Life on the Farm

Horse riding — All five of us boys had horses and rode every single day. My horse, Beauregard, stood 16½ hands tall.

Mom’s original photo

Colorized by Gemini (AI)

Dad’s honey operation — Dad kept honey bees, and we’d use a rotating machine to extract the honey.

Garden and livestock harvest — We had a huge freezer that we’d fill with vegetables from our garden, venison from Dad’s hunting, and beef from cattle we raised ourselves.

A Special Guest

One of my most memorable experiences was when Helen Berry came to live with us. Helen had been the pastor at our Congregational church but was asked to leave after she invited a Baptist minister to give a sermon one Sunday. With nowhere to go, she stayed with us for six months until she secured a position in Taiwan, where she spent 30 years. During that time, she met Chiang Kai-shek and even shared a room with Gladys Aylward—the remarkable woman who led 100 orphaned children to safety during the 1940 Japanese invasion of China, a weeks-long trek through mountains and war zones after she herself had been wounded by shrapnel.

A photo of Gladys

Another photo of Gladys and some of the children

Note: Helen took the family photo above in 1954: Susan, Donald, Mom (Barbara), David, Dad (Theodore), and me, John.

Advice for the Next Generations

Stay curious and keep learning.

The world will change faster than you expect, and often in ways no one sees coming. What will carry you through is curiosity—the habit of asking questions, of wanting to understand, of being willing to learn again and again. Travel when you can. Sit with people who don’t think like you or live like you. They will teach you more than books alone ever can. Read often. Pay attention to what is happening around you. You may not be able to fix everything, but awareness keeps you from being blindsided and helps you move through the world with open eyes.

Hold tightly to the people you love.

When life begins to wind down, almost no one wishes they had worked longer hours or bought more things. What matters are the people—the conversations, the laughter, the shared meals, the small moments that once seemed ordinary. Mothers and fathers, children and grandchildren are precious beyond measure. Siblings are threads that tie your past to your present. And friends—good friends—are the ones who walk beside you when the rest of the world is busy moving on. As time passes, your children and grandchildren will build lives of their own. Friends often become the ones who keep you company, who listen, who remind you that you still belong.

Be kind, but know your worth.

Kindness costs little and returns much. Treat everyone with respect, especially those who serve you or whose work often goes unnoticed. Tip well when you can. Help where help is needed. Feed the hungry. Lift up those who are worn down by life. But kindness does not mean surrendering yourself. Set boundaries. Protect your dignity. You can be generous without being taken advantage of.

Do work that feels meaningful.

You don’t have to change the whole world. Very few people do. But you can change someone’s world, and that matters more than you might ever know. Try to spend your days doing work that feels useful, honest, and worthwhile. Work that helps others leaves a mark long after titles and paychecks are forgotten. If you serve the public, take pride in it—you are doing work that truly matters.

Remember that pain passes.

When you’re in the middle of loss or hardship, it can feel endless. It isn’t. Life has a way of moving forward, even when you feel stuck. You are stronger than you think. As you grow older, you will lose people you care about, and that never gets easy. Grief is the price of love. The more people you love, the more loss you will know—but also the more full your life will have been.

Take care of your body.

Your body carries you through every joy and every sorrow. Treat it with care. Move it. Rest it. Feed it well. The older you get, the more you will appreciate the simple ability to walk, to breathe easily, to wake up without pain. If you care for your body now, it will give you more years of doing the things you love and being with the people who matter most.

What inspired you to start volunteering, and what has that experience meant to you?

I have volunteered my entire life.

I started young, encouraged by my parents, who led by example. My father volunteered as a Boy Scout leader and served at church in many roles, including as a deacon. He believed in showing up and helping where help was needed. We helped neighbors a lot.

My mother volunteered as well—teaching Sunday School and serving as a 4-H leader. She gave her time freely and with kindness.

Volunteering wasn’t something they talked about much; it was simply how they lived. Growing up around that, service became a natural part of my life, not an obligation. Over time, it has given me purpose, connection, and a sense of belonging. Helping others has always felt like the right thing to do—and it still does.

What Volunteering Has Meant to Me

Volunteering has been one of the most rewarding parts of my life because it allows me to learn while helping others—and to see people more clearly.

Teaching children how to build balsa-wood bridges and watching them grow in confidence is deeply gratifying. You can see the moment when something clicks, and they realize they are capable of more than they thought. Watching the audience erupt and the student stand there with pride as their bridge holds more weight than anyone else’s is awesome.

Teaching continuing education to people in the municipal sector showed me how much impact clear understanding can have. Helping them truly grasp what they were doing made their work better—and made me realize how valuable shared knowledge is.

Teaching surveying to students at the junior college level forced me to revisit the foundations of my own training. Teaching always deepens your understanding; it makes you think more carefully and appreciate the subject in new ways.

Volunteering to help foreign students has been especially rewarding. Their curiosity and generosity are contagious—and some have even invited me to visit their home countries, which is both humbling and heartwarming.

Feeding the poor taught me powerful lessons about what people value. One woman living under a bridge declined my offer of a place to stay because it would have taken her farther from her daughter and grandchildren. Others valued the freedom that street life gave them. Those experiences taught me that dignity and choice matter, even in hardship.

Serving as a Guardian ad Litem showed me how desperately some people need an advocate—someone in their corner when they have no one else. It was a sobering reminder of how fragile life can be without support.

Mentoring students in schools made it clear that many kids don’t need grand solutions. Often, they just need someone who notices them, listens, and genuinely cares.

Volunteering at shelters opened my eyes to an entirely different world—one lived by people who have very little, yet often show resilience and gratitude that stay with you long after you leave.

Teaching, in any form always pushes me to learn more than I would otherwise. And speaking publicly—giving lectures about trips I’ve taken—forces me to reflect, organize my thoughts, and remember those experiences more deeply.

Volunteering hasn’t just allowed me to give; it has continually given something back to me: perspective, humility, and a deeper understanding of people and the world.